I realize this is the dead of summer and every journalist who isn't on vacation is captivated by the Murdoch phone-hacking scandal. But while everyone is looking the other way, the National Institute of Health's proposed new rules about the disclosure of financial conflicts of interest may be watered down.

The sticking point, according to the Project on Government Oversight (POGO), is a proposed rule that would require government-funded researchers to publicly disclose potential conflicts of interest to consumers. POGO officials say that the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which has been reviewing the proposed changes for months, may weaken or eliminate the public disclosure requirement due to pressure from industry and university officials. In a letter to OMB July 11, POGO's executive director Danielle Brian and staff scientist Ned Feder called on the OMB to make sure that requirement remains in the new guidelines.

Why does this matter? Because it's vitally important for consumers to know if researchers and doctors' judgments are being swayed by industry largesse or other conflicts that could influence their work. One would think the federal agency that supports most medical research in this country (National Institutes of Health) would be playing a key role in making such conflicts of interest transparent. Think again. Even though current NIH guidelines calls for universities to report to the granting agency significant financial conflicts (more than $10,000 annually) among faculty who have NIH grants, neither the institutes nor the universities have bothered to adhere to these 16-year-old guidelines.

Case in point: Dr. Helen Mayberg, a neurologist at Emory University School of Medicine, and a principal investigator on five federally funded research projects. As I've blogged about before here and here, since she came to Emory in 2003, Mayberg has earned tens of thousands of dollars consulting for medical device companies and being an expert witness in death penalty cases, always on the side of prosecutors bent on execution. Mayberg was one of eight authors of a 2006 study who failed to disclose consulting ties with Cyberonics, the maker of the electronic device their paper touted as being effective in treating depression. Because of this egregious failure to disclose, the lead author of the study, Dr. Charles Nemeroff, then chair of psychiatry at Emory, was forced to step down as editor in chief of the journal Neuropsychopharmacology, which published the paper -- see background here.

Mayberg has also attracted notoriety for testifying (always for the prosecution) in more recent death penalty cases than almost any other doctor in the country. Mayberg's job in these cases is to raise doubts about the validity of scans that show brain damage in defendants on death row, and critics say her testimony often contradicts her own published research on brain scans. But she earns a pretty penny doing so. According to a psychiatrist who also testifies in such cases, Mayberg probably earns more than $50,000 per case. In 2009, she acknowledged testifying in at least five of these cases, which potentially adds up at least $250,000 in one year alone.

These are significant conflicts of interest that Emory should have reported to the NIMH, especially since Mayberg took over as principal investigator on two major studies that used to be led by Nemeroff: the mood and anxiety disorders initiative, a collaboration between NIMH (which put up $2.1 million last year alone) and GlaxoSmithKline, to develop a new generation of antidepressants, and another $1.8 million study called predictors of antidepressant treatment response. After Nemeroff stepped down from these NIH-funded projects in the wake of his own failures to disclose, the NIH instituted tighter rules on approving grants to Emory, including more documentation on researchers' outside activities and potential conflicts of interest, according to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Yet according to NIMH records obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, "no financial conflicts of interest were identified to NIMH by Emory University about Dr. Helen Mayberg with regard to NIH-funded research projects in which she is listed as the principal investigator." It doesn't look like the NIH has enforced its own tougher requirements in the wake of the Nemeroff affair. All I could get out of an NIH spokeswoman was this: "NIH will neither confirm nor deny matters relating to compliance which may be under review." Does that mean the failure of Emory to disclose Mayberg's myriad conflicts is under review? The NIH won't say.

This is precisely why we need a public disclosure requirement in the new regulations governing scientific conflicts of interest. Taxpayers have a right to know what their publicly funded investigators -- in the case of Mayberg, someone who is in charge of millions of dollars in grants -- are up to.

Wednesday, July 20, 2011

Monday, July 11, 2011

UPenn President is urged to resign as chair of Obama's bioethics commission for ignoring scientific misconduct allegations

The Project on Government Oversight (POGO) has called on President Obama to remove Amy Gutmann, University of Pennsylvania's president, as chair of his presidential commission for the study of bioethical issues. The reason: Gutmann did nothing to sanction the chairman of UPenn's psychiatry department for publishing an editorial under his name that was ghost-written by a medical company that worked for the drug industry. The editorial, published in Biological Psychiatry, called for the aggressive treatment of bipolar disorder on the grounds that it was linked to a number of serious diseases. In a letter to NIH Director Francis Collins last November, POGO had disclosed the ghost-writing allegation, among other egregious ghost-writing examples, and called on Collins to curb this widespread practice in scientific research.

Now, Dr. Jay Amsterdam, a psychiatrist at UPenn, has filed a new complaint with the federal Office of Research Integrity (ORI), charging that Dr. Dwight Evans, UPenn's psychiatry chair, and four colleagues (including then psychiatry kingpin Charles Nemeroff) engaged in scientific misconduct by allowing their names to be appended to a manuscript that was drafted by the same ghostwriter for GlaxoSmithKline that wrote the editorial for Evans. Amsterdam also alleges the ghost-written paper misrepresented information from a study on the use of Paxil in bipolar depression. The study in question was funded by GlaxoSmithKline and a grant from the NIMH and published in the American Journal of Psychiatry in June 2001.

In his complaint, which can be found here, Amsterdam, who was one of study 352's principal investigators, alleges that the published manuscript did not acknowledge the medical ghostwriter's contribution or the extent of Glaxo's involvement in preparing the paper. The study itself, he says, made unsubstantiated claims about Paxil's effectiveness and downplayed some serious side effects. For example, study 352 suggested that Paxil was beneficial in the treatment of bipolar disorder, when in fact it failed to show efficacy over an older antidepressant on at least one primary outcome measure. The manuscript also did not report that Paxil may have induced mania in some patients, which is a well-known side effect not only of Paxil but other SSRI antidepressants.

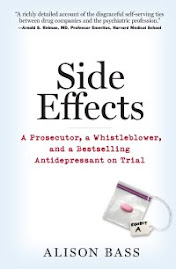

Dr. Amsterdam also alleges that even though he was a principal investigator of the study, he was excluded from the final data review, analysis and publication of the paper by the ghostwriter, Scientific Therapeutics Inc (STI). STI has a longstanding history of ghostwriting medical articles under contract to GSK and other drug companies. STI was the same company that ghost-wrote the notorious Paxil study 329, as detailed in Side Effects. Indeed, study 329 was included as one of the egregious examples of ghostwriting in POGO's letter to Collins last November, which I blogged about here.

Back in 2001, when Amsterdam repeatedly complained about not being included in the publication of his own study, one of the junior psychiatrists who had been named as an author in his place apologized to him, explaining that "control of the paper had been taken away from him and that GSK published the paper without circulating the draft to all the participants..." Amsterdam continued to assert that some sort of reprimand was necessary to ensure that "plagiarism" of a colleague's data didn't happen again. But his complaints were brushed off by Evans and other colleagues at UPenn.

In his letter to ORI, Amsterdam's attorney notes that even though study 352 was published 10 years ago, it continues to be referenced in medical journals, most recently as this year. He called on the Office of Research Integrity to conduct a thorough investigation to ensure that similar misconduct never happens again and to prevent further use of study 352 "to support the dangerous prescription of Paxil to patients diagnosed with bipolar depression."

And now back to Amy Gutmann. As chair of the presidential commission on bioethics, UPenn's president is supposed to be working to promote ethical behavior in scientific and medical research. Last November, when POGO released its letter to NIH citing the ghostwriting incident involving UPenn's psychiatry chair, the university student newspaper jumped on the story. At the time, a university spokesman was quoted in the student paper saying that allegations of ghostwriting in Evans' editorial were "unfounded." Yet documents unsealed in a lawsuit show evidence that STI prepared a draft of the editorial for Evans. Amsterdam's attorney sent Gutmann a copy of his official complaint last week; see here.

In its missive to President Obama, POGO writes:

Stay tuned...

Now, Dr. Jay Amsterdam, a psychiatrist at UPenn, has filed a new complaint with the federal Office of Research Integrity (ORI), charging that Dr. Dwight Evans, UPenn's psychiatry chair, and four colleagues (including then psychiatry kingpin Charles Nemeroff) engaged in scientific misconduct by allowing their names to be appended to a manuscript that was drafted by the same ghostwriter for GlaxoSmithKline that wrote the editorial for Evans. Amsterdam also alleges the ghost-written paper misrepresented information from a study on the use of Paxil in bipolar depression. The study in question was funded by GlaxoSmithKline and a grant from the NIMH and published in the American Journal of Psychiatry in June 2001.

In his complaint, which can be found here, Amsterdam, who was one of study 352's principal investigators, alleges that the published manuscript did not acknowledge the medical ghostwriter's contribution or the extent of Glaxo's involvement in preparing the paper. The study itself, he says, made unsubstantiated claims about Paxil's effectiveness and downplayed some serious side effects. For example, study 352 suggested that Paxil was beneficial in the treatment of bipolar disorder, when in fact it failed to show efficacy over an older antidepressant on at least one primary outcome measure. The manuscript also did not report that Paxil may have induced mania in some patients, which is a well-known side effect not only of Paxil but other SSRI antidepressants.

Dr. Amsterdam also alleges that even though he was a principal investigator of the study, he was excluded from the final data review, analysis and publication of the paper by the ghostwriter, Scientific Therapeutics Inc (STI). STI has a longstanding history of ghostwriting medical articles under contract to GSK and other drug companies. STI was the same company that ghost-wrote the notorious Paxil study 329, as detailed in Side Effects. Indeed, study 329 was included as one of the egregious examples of ghostwriting in POGO's letter to Collins last November, which I blogged about here.

Back in 2001, when Amsterdam repeatedly complained about not being included in the publication of his own study, one of the junior psychiatrists who had been named as an author in his place apologized to him, explaining that "control of the paper had been taken away from him and that GSK published the paper without circulating the draft to all the participants..." Amsterdam continued to assert that some sort of reprimand was necessary to ensure that "plagiarism" of a colleague's data didn't happen again. But his complaints were brushed off by Evans and other colleagues at UPenn.

In his letter to ORI, Amsterdam's attorney notes that even though study 352 was published 10 years ago, it continues to be referenced in medical journals, most recently as this year. He called on the Office of Research Integrity to conduct a thorough investigation to ensure that similar misconduct never happens again and to prevent further use of study 352 "to support the dangerous prescription of Paxil to patients diagnosed with bipolar depression."

And now back to Amy Gutmann. As chair of the presidential commission on bioethics, UPenn's president is supposed to be working to promote ethical behavior in scientific and medical research. Last November, when POGO released its letter to NIH citing the ghostwriting incident involving UPenn's psychiatry chair, the university student newspaper jumped on the story. At the time, a university spokesman was quoted in the student paper saying that allegations of ghostwriting in Evans' editorial were "unfounded." Yet documents unsealed in a lawsuit show evidence that STI prepared a draft of the editorial for Evans. Amsterdam's attorney sent Gutmann a copy of his official complaint last week; see here.

In its missive to President Obama, POGO writes:

We do not understand how Dr. Gutmann can be a credible Chair of the Commission when she seems to ignore bioethical problems on her own campus. Until the University concludes a sincere and transparent investigation of these charges and takes decisive action to deter future ghostwriting, we feel that Dr. Gutmann should be removed as Chair of the Commission.

Stay tuned...

Tuesday, July 5, 2011

Biederman and colleagues at Harvard get a slap on the wrist

Harvard Medical School finally wrapped up its three-year-old investigation of Dr. Joseph Biederman and two colleagues accused of failing to disclose extensive financial conflicts of interest, with essentially a slap on the wrist.

In 2008, Congressional investigators accused the three psychiatrists -- Biederman, Thomas Spencer and Timothy Wilens -- of failing to disclose more than $1 million each in payments from the drug industry. As I blogged about here, most of Biederman's financial ties were with the makers of anti-psychotic drugs at the very same time he was promoting the use of these drugs in the treatment of childhood bipolar disorder. According to documents released in a lawsuit, Biederman also courted funding from Johnson & Johnson by promising that his work at Mass. General would promote the use of its anti-psychotic Risperdal in children. Johnson & Johnson gave the hospital $700,000 for a Biederman-led research center that did studies promoting Risperdal. All of which raises the question of whether Biederman helped the drug company illegally market the off-label use of its anti-psychotic drug in children

But rather than suspend or fire him for such unethical and possibly criminal behavior, Harvard and Mass. General let him and his two colleagues off easy. According to The Boston Globe, they required the three physicians to refrain from all paid industry-sponsored activities for one year and undergo unspecified additional training. A letter Biederman and his colleagues wrote to co-workers about the remedial actions also mentioned that they might "suffer a delay of consideration for promotion and advancement."

Wow, that's tough. As Dr. Jerome Kassirer, a Tufts University professor and author of On the Take, notes in The Globe article, Biederman already is a full professor at Harvard so it's unclear how a delay in promotion would affect him. This strikes me as one more example of how hospitals and medical schools are so compromised by drug company money themselves that they no longer care to impose ethical standards on their own faculty.

On a sadly related note, the mother of Iris Chang, a bestselling author and historian who killed herself in 2004, reveals in a new memoir that her daughter was taking psychoactive drugs that may have caused her suicide. Iris Chang was the author of The Rape of Nanking, a critically acclaimed history of the massacre of Chinese men, women and children by Japanese soldiers in the run-up to World War II. She was only 36 when she died and the mother of a two-year-old boy.

In her memoir, The Woman Who Could Not Forget, Ying-Ying Chang, reveals that Iris was taking Risperdal and the antidepressant Celexa, when she killed herself. Chang's mother writes that she believes Iris' suicide was caused by her medications. She calls attention to the extensive literature showing that SSRI antidepressants cause suicidal behavior in some patients (often in the days after they first start the drugs), and she notes that Iris had begun taking Celexa right before she shot herself in October 2004.

Her mother writes:

In 2008, Congressional investigators accused the three psychiatrists -- Biederman, Thomas Spencer and Timothy Wilens -- of failing to disclose more than $1 million each in payments from the drug industry. As I blogged about here, most of Biederman's financial ties were with the makers of anti-psychotic drugs at the very same time he was promoting the use of these drugs in the treatment of childhood bipolar disorder. According to documents released in a lawsuit, Biederman also courted funding from Johnson & Johnson by promising that his work at Mass. General would promote the use of its anti-psychotic Risperdal in children. Johnson & Johnson gave the hospital $700,000 for a Biederman-led research center that did studies promoting Risperdal. All of which raises the question of whether Biederman helped the drug company illegally market the off-label use of its anti-psychotic drug in children

But rather than suspend or fire him for such unethical and possibly criminal behavior, Harvard and Mass. General let him and his two colleagues off easy. According to The Boston Globe, they required the three physicians to refrain from all paid industry-sponsored activities for one year and undergo unspecified additional training. A letter Biederman and his colleagues wrote to co-workers about the remedial actions also mentioned that they might "suffer a delay of consideration for promotion and advancement."

Wow, that's tough. As Dr. Jerome Kassirer, a Tufts University professor and author of On the Take, notes in The Globe article, Biederman already is a full professor at Harvard so it's unclear how a delay in promotion would affect him. This strikes me as one more example of how hospitals and medical schools are so compromised by drug company money themselves that they no longer care to impose ethical standards on their own faculty.

On a sadly related note, the mother of Iris Chang, a bestselling author and historian who killed herself in 2004, reveals in a new memoir that her daughter was taking psychoactive drugs that may have caused her suicide. Iris Chang was the author of The Rape of Nanking, a critically acclaimed history of the massacre of Chinese men, women and children by Japanese soldiers in the run-up to World War II. She was only 36 when she died and the mother of a two-year-old boy.

In her memoir, The Woman Who Could Not Forget, Ying-Ying Chang, reveals that Iris was taking Risperdal and the antidepressant Celexa, when she killed herself. Chang's mother writes that she believes Iris' suicide was caused by her medications. She calls attention to the extensive literature showing that SSRI antidepressants cause suicidal behavior in some patients (often in the days after they first start the drugs), and she notes that Iris had begun taking Celexa right before she shot herself in October 2004.

Her mother writes:

"[Iris] represented a classic case in which psychiatric medications change one's personality. I do not need to repeat the huge number of bizarre cases documented, in which an originally ordinary mildly depressed patient becomes violent and destructive after taking antidepressants...The tragic violent way she ended her life was not characteristic of Iris."Ying-Yang said she hopes her memoir "will help people become aware of the possible danger of psychiatric drugs and to think twice before taking them."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)