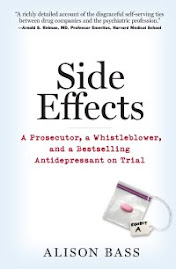

Sad to say, actual retractions may be the tip of the iceberg. Consider the 2001 study of Paxil in adolescents, the subject of my book, Side Effects. According to a recent article in the British Medical Journal, two academic researchers have called on the journal that published the Paxil trial, known as study 329, to retract it because of the way its authors manipulated and omitted data to make Paxil look safer and more effective in adolescents than it really was. As I reported in Side Effects and subsequent blogs, Dr. Martin Keller, then chief of psychiatry at Brown University and the lead author of this study, miscoded several teenagers who had become suicidal as a result of taking Paxil as being noncompliant instead of as developing adverse side effects from the drug. In addition, Keller and his co-authors concluded that Paxil was effective in treating depression when in fact the drug was not more effective than a placebo on either of the two primary outcome measures of the study and most of the original secondary outcome measures.

As the BMJ article notes:

The drug only produced a positive result when four new secondary outcome measures, which were introduced following the initial data analysis, were used instead. Fifteen other new secondary outcome measures failed to throw up positive results.

It is important to note here that Keller, along with most of the co-authors of this paper, had lucrative consulting or speaking arrangements with GlaxoSmithKline, the maker of Paxil, the full extent of which they failed to disclose when the paper was published. Indeed, as I reported in Side Effects, the 2001 paper itself was ghost-written by Scientific Therapeutics Information (STI), a medical company hired by GlaxoSmithKline and the same one that helped the former psychiatry kingpins Charles Nemeroff and Alan Schatzberg write an entire psychiatric textbook promoting Paxil, according to the New York Times.

Even though peer reviewers for the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry said that the results of study 329 did not show efficacy for Paxil and had a host of other methodological problems, the journal accepted the study for publication anyway. One wonders whether the fact that one of the co-authors, Dr. Graham Emslie, was on the journal's board at the time had anything to do with its precipitous publication in July 2001.

Before making the decision to put black box warnings about increased suicidal risk of Paxil and antidepressants in children and young adults in 2004, the FDA looked closely at study 329 and concluded that its conclusions were indeed misleading and did not demonstrate the drug's efficacy over placebo; read about this here.

Two academic researchers, Dr. Jon Jureidini,associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Adelaide, and Leemon McHenry, lecturer in philosophy at California State University, are now calling for the retraction of this study, which was used by Glaxo to heavily market Paxil to doctors treating depression in children and adolescents.

As the BMJ piece notes, the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) recently advised journal editors to retract a paper if “they have clear evidence that the findings are unreliable.” If any published paper fits this category, study 329 does.

Hat tip to Neuroskeptic for making me aware of the BMJ article.